Late Presentation of Life-threatening Tracheostomy Hemorrhage

Introduction

Hemorrhage from or around a tracheostomy is a relatively common and possibly life-threatening complication. Complications from a tracheostomy can be early or late and can be related to the placement of the tube, prolonged time duration of tracheostomy tube requirement, or abnormal healing at the surgical site. Tracheo-arterial fistulas represent a rare but often lethal complication from tracheostomies. This case report describes a patient who developed a fistula between a mature tracheostomy site and the innominate artery. The report discusses important practical considerations for preoperative and intraoperative management of this condition and describes the most common risk factors, diagnostic approach, and surgical technique.

Case Summary

A 73-year-old man with a past medical history of diabetes mellitus type 2 and coronary artery disease presented complaining of blood-tinged tracheal secretions from a tracheostomy site. Open surgical tracheostomy had been performed four months prior, after he was unable to be weaned from mechanical ventilatory support following a coronary artery bypass graft surgery. No complications were reported at the time of the original procedure, and there was no evidence of herald bleeding.

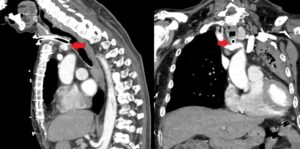

Given the complex medical history and risk factors, it was decided to perform a revision of the tracheostomy in the operating room. Upon induction of general anesthesia and orotracheal intubation, the tracheostomy cannula was removed, producing immediate brisk, pulsatile bleeding evidenced at the stoma site. Multiple conservative hemostatic maneuvers were attempted without success. Ultimately, surgical exploration of the neck and superior chest was performed, and a fistula between the trachea and the brachiocephalic trunk was identified. Surgical repair was achieved using a bovine pericardial patch with a sternohyoid muscle flap. The patient was subsequently transferred to the ICU for further hemodynamic management and airway protection. Preoperative head and neck CT scan demonstrate images consistent with the findings described (Fig 1 a & b).

Case Discussion

Tracheo-arterial fistulas are uncommon, potentially fatal complications of tracheostomies. Rates of 0.1–1% after surgical tracheostomy have been reported, with a peak incidence at 7–14 days post-procedure. Although, they often occur 2-3 weeks after tracheostomy, late presentation, as seen in this case, is also possible. Hemorrhage occurring 3 days to 6 weeks should be considered as trachea-innominate fistula until proven otherwise. A sentinel bleed is reported in 50% of cases that go on to develop delayed massive hemorrhage.

The most commonly involved vessel is the innominate artery1. Commonly identified causes include a high-riding tracheo-innominate vessel, low-lying tracheostomy (lower than the 3rd tracheal ring), mucosal necrosis from sustained high cuff pressures or direct mucosal trauma from a tube that is excessively long or wide 2. The presence of infection, hypotension, malnutrition, or corticosteroid use was also reported as potential risk factors3.

This entity should be prioritized in the assessment of airway bleeding in tracheotomized patients as it is associated with exceedingly high mortality rates. Thus, it is of utmost importance for the perioperative care team, to thoroughly review available imaging, including CT scans, to better understand the specific anatomic variations associated with individual prosthetic airways.

Adequate oxygenation is the central component of immediate management with simultaneous identification and termination of bleeding. Prompt recognition and surgical control of bleeding are crucial for patient survival 3. Initial temporizing measures include overinflation of the tracheostomy cuff, external pressure over the sternum and application of direct pressure (anteriorly) with a finger via the stoma once the airway is secured. Although management classically involves ligation of the innominate artery, in some cases, surgical repair may be preferable 4.

Fig1: Computed tomography (with intravenous contrast on arterial phase) demonstrating tracheo-innominate fistula.

References

- Scalise, P., Prunk, S. R., Healy, D. & Votto, J. The incidence of tracheoarterial fistula in patients with chronic tracheostomy tubes: a retrospective study of 544 patients in a long-term care facility. Chest 128, 3906–3909 (2005).

- Fernandez-Bussy, S. et al. Tracheostomy Tube Placement: Early and Late Complications. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 22, 357–364 (2015).

- Reger, B., Neu, R., Hofmann, H.-S. & Ried, M. High mortality in patients with tracheoarterial fistulas: clinical experience and treatment recommendations. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 26, 12–17 (2018).

- Jones, J. W., Reynolds, M., Hewitt, R. L. & Drapanas, T. Tracheo-innominate artery erosion: Successful surgical management of a devastating complication. Ann Surg 184, 194–204 (1976).