A Brief Conversation with…Jeffery S. Vender

Jeff Vender, MD, MCCM, MBA is the Emeritus, Harris Family Foundation Chairman of the Department of Anesthesiology at NorthShore University HealthSystem in Evanston, Illinois and a Clinical Professor at the University of Chicago Pritzker School Of Medicine. Dr. Vender was the recipient of the SOCCA Lifetime Achievement Award in 2018.

Jeff Vender, MD, MCCM, MBA is the Emeritus, Harris Family Foundation Chairman of the Department of Anesthesiology at NorthShore University HealthSystem in Evanston, Illinois and a Clinical Professor at the University of Chicago Pritzker School Of Medicine. Dr. Vender was the recipient of the SOCCA Lifetime Achievement Award in 2018.

What influences early in your career led you to become a critical care anesthesiologist?

My first exposure to anesthesiology was as a medical student where I was inspired and impacted by key leaders and mentors in the field. Barry Shapiro led the anesthesia critical care program at Northwestern, and he was a wonderful teacher, clinician, mentor (and friend) who demonstrated that critical care offered an appealing avenue of engagement and continuity of care beyond the operating room with patients, families, and other clinicians.

Many leaders in our specialty can typically point to a few key mentors during their careers who helped to shape their trajectory. How did you develop relationships with these individuals?

I would first like to credit my mother and her unabashed positive outlook on life and unconditional love. She was unwavering in her belief that you could accomplish what you wanted with persistence and dedication. Professionally speaking, I had the opportunity to work with many great clinicians during training, including James Eckenhoff. Jim was a renowned anesthesiologist and the Dean of the medical school at Northwestern. He had a bigger than life personality, and he challenged everyone who worked with him in the operating room. Jim influenced me to reach beyond clinical anesthesia to other important opportunities: leadership, scholarship, and professional engagements. Later in my life, I encountered two superb business school professors, Robert (Bob) Duncan and J. Keith Murnighan, who were both involved in teaching leadership and organizational behavior. They further inspired me to seek ways to participate in organizational change and leadership.

You have lectured extensively on the importance of leadership in medicine. Could you speak to its importance for critical care physicians?

Leadership is important everywhere but especially so in an intensive care unit or operating room. These are high-reliability organizations where everyone must be engaged in their roles and have a sense of their own contribution to overall success, regardless of hierarchy or title. If you want a great intensive care unit it has to be built from the foundation up. To me that foundation means phenomenal nursing, and other key support staff, who are committed to patient-focused care and willing to go beyond boundaries. Championing education and developing interpersonal relationships further contribute to this foundation. We have a shortage of leaders in medicine, but leadership is critical when the stakes are high and the circumstances necessitate vigilance, competence, and passion for the care and treatment of the critically ill.

What other factors do you think are responsible for this dearth of leaders in medicine?

Medical school admissions are largely predicated on individual achievement and deemphasize traits that are of critical but difficult to quantify or extract from a CV: integrity, perseverance, passion, critical thinking, interpersonal skills, and so on. Physicians are often individualistic and, in contrast to high-performers in other domains, unaccustomed to a focus on teamwork. This can beget poor engagement in leadership roles and a failure to appreciate the importance of empathy, listening to understand, self-awareness, and self-regulation, which ultimately lead to effective leadership.

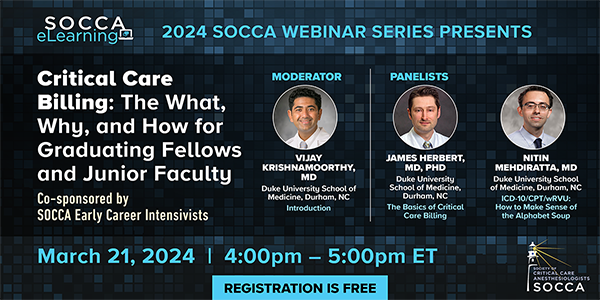

How can fellows and junior faculty, some of whom will seek out or be asked to assume leadership roles in critical care environments, evolve into effective leaders?

The first skill you need for leadership is competency, and for physicians this means initially allowing time for clinical development. Once you demonstrate clinical competency, leadership opportunities will often begin to emerge, and then developing leadership competency is key. Physicians are intelligent and not apt to follow an incapable leader. Leadership should not be about titles and additional income. It should be borne from a genuine interest in serving others. Identifying mentors is the first step. Reading, attending lectures of leadership and coursework are all next steps. One key early lesson is to appreciate the importance of personal growth: understanding weaknesses and strengths, seeking feedback to enhance self-awareness, and regulation of behavior. Effective leaders utilize the strengths of others, which is a challenge for some physicians. Finally, never be afraid to ask for help. Seeking guidance too late is a common pitfall, which may lead to preventable adverse events.

Mentorship again emerges as a central theme here. What practical advice would you have for fellows or junior faculty who are struggling to identify mentors?

A mentor should be someone who you respect for all the right reasons, and they should command respect, not demand it. When opportunities within a department or division are sparse, get involved more broadly within the institution. Significant, rapid, or consequential change never happens successfully in the absence of effective leadership, because our inherent tendency is to resist change. If you place yourself in engagements where change is occurring, you will see if it is successful or not, which can offer the opportunity both to learn and identify mentors.

What would you consider to be your greatest accomplishment?

I was able to obtain a modicum of professional successes and recognitions while enjoying a marriage of 45 years to my phenomenal wife Bobbie; a caring relationship with my two children, Kim and Todd (and their spouses Steve and Jeannine); and my grandchildren Ryan, Margaux, Gavin, Wiley, Pierce, and Jeffery (Jack). I think sometimes we forget what is really important in our lives. We talk about work/life balance and burnout, and we all over-commit at times. We lose sight that balance is necessary for success, and my family was always my first priority even though there were times that they sacrificed for me. You cannot lose sight that no award or recognition is ultimately worth certain sacrifices. Similarly, I have been blessed with a great professional family. My outstanding associates in anesthesia at NorthShore University HealthSystem enabled and supported me to go farther than I thought I would have gone. In addition, their successes have made me feel like a proud parent, and I am grateful for being part of a team in the operating room and intensive care unit that pursued excellence and positively impacted outcomes for patients, the institution, and our profession. These outcomes are not unique to me or our team, but they continuously reinforce why we all do what we do.

Any closing words of wisdom for fellows or junior faculty in our specialty?

Critical care is a fantastically appropriate venue for anesthesiologists and a natural off-shoot of the field of anesthesia. We are the in-hospital physicians and are accustomed to performing in high-reliability environments and managing critically ill patients in all specialties. Challenges in critical care lie ahead: supporting manpower needs in an economically feasible way, rebalancing care to reflect both value and quality, and reshaping how we approach the end of life. Although clinical care in the intensive care unit seems to have changed little during my career, our ability to work in teams and deliver timely interventions has certainly become more evident. Anesthesiologists are well-positioned to tackle these challenges and be leaders in critical care.