Women in Critical Care Feature: Understanding and Overcoming Imposter Phenomenon

by Crystal Manohar, MD, MBA, FASA

Imposter phenomenon (IP) was first described by Drs. Clance and Imes in 1978 in highly successful women who have an “inability to internalize [their] accomplishments” despite evidence to the contrary. Instead, they hold tight to the notion their “successes are fraudulent” and “are convinced that they have fooled anyone who thinks otherwise.” (1) Imposter phenomenon (also known as imposter syndrome) is an established entity seen in both men and women and is not uncommon in medicine. In fact, IP is more prevalent among physicians than the general population with a prevalence of 22-60% in medical students and 33-44% in residents. (2) Further, A European survey from 2024 explored IP in Anesthesiology and found high rates of IP in physicians identifying as female and physicians with fewer years of practice. (2)

IP may be attributed to many factors including outward recognition creating fear that an individual cannot live up to future expectations. Additionally, in medicine in particular, physicians are surrounded by many other high achieving individuals which leads to peer comparison and loss of appreciation of one’s own successes. (3) Drs. Clance and Imes also explored behaviors that maintain IP such as intellectual flattery (favoring other’s opinions instead of asserting one’s own beliefs/ideas which reinforces IP) and utilizing charm and perceptiveness to win over superior’s approval (thereby minimizing the development of internal confidence). Finally, a fear of negative consequences may contribute to continued IP experiences. For example, female critical care physicians may serve as team leaders and display confidence in their abilities during crisis situations (such as cardiac arrest in the ICU). This behavior may not be accepted as “expected of a woman” and is instead interpreted as hostile, assertive or aggressive. This perceived “negative behavior” then reinforces IP and results in individuals avoiding such behaviors in the future.

The consequences of IP are numerous and widespread and can include low self-esteem, confidence and insecurity. Fear of failure is also common as individuals wait to be discovered “as an imposter.” IP can lead to a self- perpetuating cycle which limits an individual’s willingness to seize opportunities and thus, imposes possible barriers to career development, leadership roles, promotion and even salary raises. IP has also been correlated to increased burnout and decreased job retention. (4)

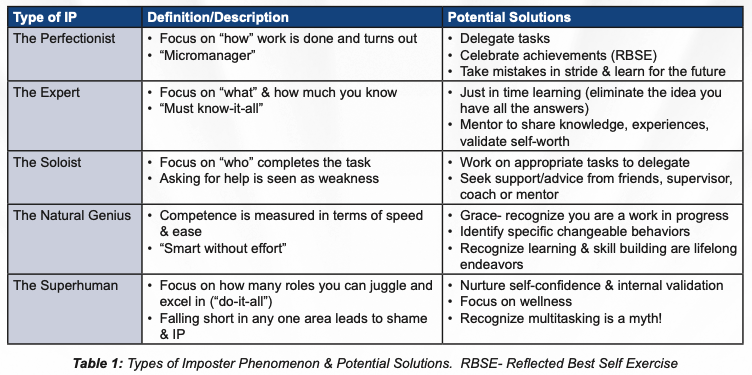

Given its prevalence and problematic nature, it is imperative we find and implement solutions to treat IP. A first step to recognize and quantify an individual’s imposter phenomenon experience is by using the Clance Imposter Phenomenon Scale (CIPS). (5) The CIPS is a validated tool to assess imposter syndrome and investigates feelings of competency, praise and success. (2) It is also worthwhile to explore the five types of IP described by Dr. Valerie Young in her book “The Secret Thoughts of Successful Women,” which is based on research from ample people in a variety of occupations at all phases in their careers (6). Understanding the various types of IP and which one(s) may be pertinent to an individual will aid in determining viable solutions (table 1).

Ultimately, a multipronged approach is best employed to address IP. Key solutions include celebrating achievements, having grace for oneself, and nurturing self-confidence and internal validation. A mentor will be valuable to share knowledge, experiences and to validate self-worth. The Reflected Best Self Exercise (RBSE) utilizes a “personal highlight reel or living eulogy” to help combat IP and has been used with benefit in resident training. (7). Role playing may provide an opportunity to discuss perception versus reality and help normalize failures while encouraging individuals to pursue new opportunities. Systemic contributions such as increasing diversity and promoting gender equality in the workplace are also essential to help address IP. Finally, though we remain susceptible to IP throughout our career(s), by continually monitoring for IP and practicing the solutions above, we protect ourselves and our colleagues when IP strikes.

REFERENCES:

- Pauline Rose Clance & Suzanne Ament Imes, “The Imposter Phenomenon in High Achieving Women: Dynamics and Therapeutic Intervention.” Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, & Practice 15, no. 3 (1978): 241-7.

- Gisselbaek M, Hontoir S, Pesonen AE, Seidel L, Geniets B, Steen E, Barreto Chang OL, Saxena S. Impostor syndrome in anaesthesiology primarily affects female and junior physicians☆. Br J Anaesth. 2024 Feb;132(2):407-409. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2023.09.025. Epub 2023 Oct 25. PMID: 37884406.

- Baumann N, Faulk C, Vanderlan J, Chen J, Bhayani RK. Small-Group Discussion Sessions on Imposter Syndrome. MedEdPORTAL. 2020 Nov 10;16:11004. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374- 8265.11004. PMID: 33204832; PMCID: PMC7666839.

- Mirjam Neureiter and Eva Traut-Mattausch, “Inspecting the Dangers of Feeling Like a Fake: An Empirical Investigation of the Impostor Phenomenon in the World of Work,” Frontiers of Psychology (2016), https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01445.

- https://paulineroseclance.com/pdf/IPTestandscoring.pdf

- https://impostorsyndrome.com/articles/5-types-of-impostor- syndrome/

- Rydberg MG, Appleton LK, Fried AJ, Cable DM, Bynum DL. Implementation of a “Best Self” Exercise to Decrease Imposter Phenomenon in Residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2024 Jun;16(3):308- 311. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-23-00873.1. Epub 2024 Jun 13. PMID: 38882411; PMCID: PMC11173007.