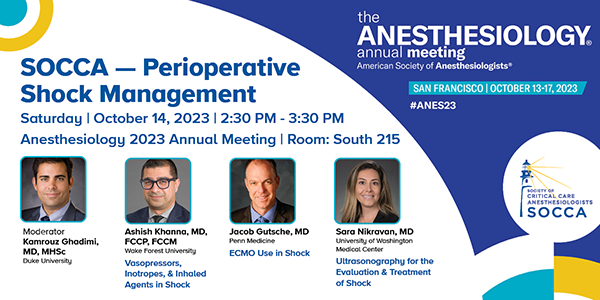

“Is There a Doctor on Board?” A Primer on In-Flight Emergencies and Q&A with Dr. Ashish Khanna

In-flight medical emergencies (IMEs) are estimated to occur in 1 of every 604 flights; given the tremendous volume of global air travel, 260 and 1420 IMEs may occur daily.1 Invariably, these events take place in a complex setting characterized by limited information and equipment. Many physicians have little personal experience responding to in-flight crises, and even seasoned anesthesiologist-intensivists will likely find these events challenging and stressful. This article briefly overviews clinical, logistical, and legal considerations relevant to managing in-flight medical emergencies.

Likely Clinical Scenarios

Decreased air pressure, oxygen tension, immobility, and dehydration may predispose vulnerable patients to IMEs, particularly on longer-duration flights.2, 3 The most common medical events include syncope or near syncope (30%), gastrointestinal illness (15%), respiratory distress (10%), cardiovascular symptoms (7%) and stroke- or seizure-like symptoms (up to 5%, each).1 Less frequent are trauma (5%), psychiatric symptoms (3%), substance abuse (3%), allergic reactions (2.3%), obstetric emergencies (1%), and cardiac arrest (0.2%).1

Unsurprisingly, medications and medical equipment available in flight tend to be limited. While airlines may choose to stock additional materials on board, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) minimum standards for emergency medical kits include limited quantities of IV access supplies, as well as PO and IV antihistamines, aspirin, nitroglycerine, and injectable epinephrine.1 International standards vary.3

Although IME patient mortality is reportedly low (0.2%), serious morbidity is less well described. Flight diversions are required only in a minority of cases (4-13%).2, 4

IME Logistics

Physicians who respond to an IME are not expected to work alone. Flight crews are familiar with airline emergency protocols and are frequently trained in basic first aid, CPR, and AED use.4 Serious medical events also warrant crew consultation with a ground-based physician affiliated with the airline or with a hired consultancy.3 Indeed, a majority of IMEs are managed by flight crews and ground-based medical support without the assistance of on-board volunteers.1

Published data indicate that physicians represent approximately 50% of on-board IME responders, suggesting that nurses, emergency medicine technicians (EMTs) and midlevel providers are also often available to help provide care.2 Ideally, IME volunteers will contribute their skills and defer to the recommendation(s) of the volunteer with the most relevant expertise. While stabilizing and managing a patient, clear and open communication with the flight and ground crews is essential.3 In high-acuity situations, the consulting ground-based physician issues the final guidance regarding care, including the recommendation to divert the flight.1 The captain of the aircraft is responsible for the decision to divert.

Medicolegal Considerations

Many physicians may feel ethically obligated to respond to an IME. They may also feel confusion or concern regarding their legal responsibilities and protections. In the US, physicians are not required to respond to in-flight medical crises.1 By contrast, several European countries and Australia do require physicians to offer their services, consistent with domestic civil and case law. Barring gross negligence or willful misconduct, US law affords IME responders protection under the “Good Samaritan” clause of the Aviation Medical Assistance Act.2

Of note, Good Samaritan status may be jeopardized if the physician accepts monetary or non-monetary compensation from the airline, including but not limited to mileage points, seat upgrades, and travel vouchers.5 Obviously, a physician should not respond if intoxicated or otherwise incapacitated during the flight. Overall, litigation against IME volunteers is extremely rare, with some sources citing a single documented lawsuit between 1998 and 2017.2 Indeed, a recent JAMA article concluded that “medical assistance rendered by a capable physician is of little personal legal risk and is supported by experts in aviation medicine.”1

Conclusion

Due to the growing volume of air travel, including long-haul flights, in-flight medical emergencies are relatively common and are likely to become even more frequent. These events pose unique challenges for physician volunteers, including anesthesiologist-intensivists. When considering whether to volunteer their services, physicians may benefit from the knowledge that on-ground medical support is available, that clear and open communication with the flight crew is essential, and that medicolegal liability is limited.

Responding to an IME

Recently, Dr. Ashish Khanna responded to an in-flight medical emergency on an international flight. Dr. Khanna helped to stabilize a teenage patient who seemed to have had a severe allergic reaction to food served in flight. Dr. Khanna recommended that the pilots divert the plane and land before crossing the Atlantic. The patient was evacuated and received on the tarmac by an awaiting medical crew.

Dr. Khanna answered the following questions regarding this recent event.

SOCCA Interchange (SI): What, if anything, surprised you about the experience of responding to an in-flight medical emergency?

Dr. Ashish Khanna (AK): When I heard the overhead message “we need a medical doctor,” I was not surprised. These things happen commonly on transcontinental flights. The most common problems are things like hypoglycemia in diabetics, an extra drink or two and feeling unwell, or at most a non-cardiac chest pain. This was different in that it was a child accompanied by a mother, who was herself travelling alone with two other younger kids, and who knew what was happening. By the time I saw the patient, he was clutching his neck and complaining that his chest was tight and that his throat was closing. I did not have a lot of time to think through the situation.

After administering an Epi-pen, I asked the crew, out of my naiveté, if they had any airway equipment on board. I was surprised when they said no. Furthermore, I was surprised that they did not carry much to specifically control a potential anaphylaxis situation, e.g., no IV or oral steroids and no bronchodilators. We gave oxygen from the emergency oxygen tanks and used the bronchodilators and epi-Pens that the mom carried. After I established IV access, we gave diphenhydramine and metoclopramide. We had portable blood pressure and oxygen saturation monitors, which was nice.

I was pleasantly surprised by the teamwork and help offered by the flight crew, co-passengers, and even the captain. I was assisted by a pediatric surgeon and a nurse who were also on the flight. Teamwork was critical, as was crowd control and quick assessment of the situation. I am thankful that we had a supportive and motivated team that did their best to help at all times during the crisis.

SI: What advice would you offer your fellow Intensivists, and particularly more junior colleagues, who might find themselves in a similar situation in the future?

AK: Assess the situation and take control. There is chaos, but you as critical care doctors, and specifically with a background in anesthesia, are the best equipped to run these as a team leader. Ask the crew and staff all your questions regarding supplies and what’s available and what’s not. Ask these questions early so you can plan your next move.

If the situation escalates, as it did here—the teenager did not respond to an initial round of interventions—talk to the captain to know where you are geographically and what you should advise the captain in the context of the patient. In this case, I took a somewhat conservative decision to suggest that we divert to London instead of making the North Atlantic crossing with an unstable patient. I knew the patient would ultimately respond to treatment, but he could have also declined further. Once on the North Atlantic crossing, the nearest landmass would be 6 hours away. With no other resources, we could have been in a true emergency—for instance, needing an advanced airway and further equipment, but with nothing available to escalate.

In short, my most important advice would be to be conservative and practice safe medicine when in such a situation. In retrospect, continuing on our way would have saved everyone a lot of hassle with flight cancellations, delayed returns to work, and missed connections. However, the flip side would have been a non-salvageable emergency over the mid-Atlantic. I would not have been able to forgive myself for that poor choice later on.

SI: In what ways was managing the in-flight emergency most similar to, and most different from, your daily work as an Intensivist?

AK: If this had been my patient in the ICU, I would have felt very much in control and not worried after administration of initial meds. Even if the response to medications had been less than robust, as it was here, I would be thinking about the next round of interventions and what I might need to do in case of further problems. This is where this situation was the same and yet different: all I had was a medicine box and basic supplies. I knew that these interventions needed to work. If they did not, I had nothing to fall back upon. From that perspective, this was stressful since the onus was on me, and I had to make 100% certain that my choice, even though defensive at the time, was the right choice for the child and his family.

SI: What critical care knowledge and skills were most valuable in managing this in-flight emergency?

AK: In terms of the basics, assessment of cardiorespiratory status during an acute anaphylactic reaction, management of acute severe bronchospasm, and initiation of IV access with fluid resuscitation.

SI: How did you navigate sharing clinical decision-making responsibility with other physicians who responded in-flight, and with the airline physician on the ground?

AK: I was put in touch with American Airlines ground control in Dallas, where I spoke with another physician. I did not know this at the time but I was told later that the physician on the ground takes over all liability since this person is employed by AA for exactly this purpose. The physician on the ground did rely heavily on me for my best judgment but definitely endorsed my call for the diversion once we reached a stage where the child did not seem to be responding to our initial interventions. The other team members (a pediatric surgeon from Chicago and a nurse from NYC) were constantly working with me, checking vitals, reassessing the child, and, most importantly, reassuring his mother that all would be okay.

SI: What, if anything, would you do differently in responding to a similar situation in the future?

AK: Every situation is different, and it’s difficult to say what I would do for a similar situation in the future. There is nothing I would have really done very differently.

SI: Is there anything else you would like to add about this experience?

AK: Some things are “meant to happen.” Is it a true coincidence that I wore my SCCM [Society of Critical Care Medicine] shirt on the flight? I also had a bunch of rescue oxygen cylinders in the overhead bin exactly above my seat. I jokingly gestured to my co-passenger as I boarded, “I will not need these tonight - will I?” This was one such day when all these signs pointed to me and a day where I truly felt proud to be an anesthesiologist-intensivist. I love the specialty and would choose this many times over if given the chance!

References

Martin-Gill C, Doyle TJ, Yealy DM. In-Flight Medical Emergencies: A Review. Jama. 2018;320:2580-2590.

Hu JS, Smith JK. In-flight Medical Emergencies. Am Fam Physician. 2021;103:547-552.

Kodama D, Yanagawa B, Chung J, Fryatt K, Ackery AD. “Is there a doctor on board?”: Practical recommendations for managing in-flight medical emergencies. Cmaj. 2018;190:E217-e222.

Cocks R, Liew M. Commercial aviation in-flight emergencies and the physician. Emerg Med Australas. 2007;19:1-8.

de Caprariis PJ, DiMaio A. In-flight Medical Emergencies and Medical Legal Issues. Am Fam Physician. 2021;104:443.