Critical Care Anesthesiologists: Their Expanding Role Outside the ICU

The first public demonstration of an ether anesthetic in 1846 marked a turning point in our ability to provide safe and effective medical care. It birthed the specialty of anesthesiology as we know it today.1 While the footprint of anesthesiology has classically centered around the operating room, its practitioners quickly began bringing the expertise gained therein to other settings such as obstetrics, pain management, and critical care. Today, we are seeing a similar burgeoning of the depth and scope of the practice of critical care anesthesiologists (CCAs) beyond their traditional roles in the intensive care unit (ICU).

CCAs bring many skills and experiences that can help bridge perioperative medicine with broader areas of patient care. Our background in anesthesiology already positions us as expert consultants in patients’ medical and logistical needs across the continuum of preoperative, intraoperative, and immediate postoperative care. In the ICU, we gain the perspective of providing longer-term care for the critically ill, patients on the floor and in the emergency room, those ready for discharge or transfer to the floor, or those moving to skilled nursing care or rehabilitation facilities. We bring firsthand knowledge of multiple distinct but interconnected systems beyond the operating room and ICU, including resource management, care coordination, discharge planning, social work, billing, insurance, and more. Let us consider several examples.

The perioperative surgical home (PSH) was introduced as a concept by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) in 2011 as a patient-centered, continuity-focused model of care intended to bridge the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative needs of surgical patients.2 This model is increasingly being utilized everywhere, from tertiary care centers to community hospitals, as our aging population brings with it a higher incidence of medically challenging patients presenting for surgery.3 With this comes an increasing need for physicians skilled in managing highly comorbid patients. CCAs are often tasked with caring for such patients in the operating room and serving as their care providers in the ICU. We can leverage this expertise to predict complications and optimize care in ways ranging from preoperative adjustments of medications, nutrition, and conditioning to invasive intraoperative cardiac monitoring to postoperative ventilator management, all while maintaining greater continuity of care than might otherwise be impossible.

A 2019 study estimated that nearly 300,000 in-hospital cardiac arrests occur annually in the United States.4 Multiple national and international committees have suggested Rapid Response Systems (RRS) as a means of improving outcomes following in-hospital cardiac arrest.5 The involvement of intensivists in such teams has been shown to have beneficial effects on several post-arrest metrics.6 CCAs may aid in the success of these teams by (1) helping identify patients early in the course of their deterioration, (2) offering immediate recommendations on early intervention, and (3) assuming care either in the ICU or until definitive disposition is available. The involvement of CCAs in such teams may be particularly valuable in rural communities or developing nations. By acting as a singular source of hemodynamic, airway, sedation, and vascular access expertise, we can help overcome the limited availability of all these modalities in under-resourced settings.

For patients failing to respond to maximal medical therapy during cardiovascular collapse, initiation of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) may be a crucial bridge to definitive treatment. While the operating room of a tertiary care center is the optimal environment for such placement, ECMO is increasingly being initiated in the ICU, on the floor, and even at smaller regional and local hospitals before transport to a referral center. The International ECMO Network recommends the development of mobile teams to help coordinate such processes and, if necessary, provide on-site support and transport back to an experienced ECMO unit.7 To safely implement ECMO in such a broad context requires not just skilled proceduralists but knowledgeable consultants advising on the candidacy of individual patients and optimization before, during, and after cannulation. While this has classically fallen to cardiothoracic surgeons, CCAs are increasingly being called upon to fill this role.8 Our understanding of cardiovascular and respiratory failure, skills with echocardiography, and vascular access expertise position us to quickly identify patients likely to benefit from ECMO, locate and cannulate target vessels, and continue management throughout transport and in the ICU.

CCAs can also help guide decision-making in the realm of palliative care and when high-intensity care would prove futile and, in turn, increase patient suffering. Staying in an ICU during the last 30 days of life and death in an acute care setting are considered negative prognosticators of the quality of end-of-life care.9 Patients nearing the end of life frequently have complex medical histories, significant analgesic requirements, and complicated family/surrogate needs, and the availability of dedicated palliative care services is often limited.10 But this is precisely the population CCAs are best trained to serve. A 2018 randomized control trial showed that ICU-led family support interventions with patients nearing end-of-life and their surrogates resulted in improved quality of communication ratings and reduced ICU length of stay.11 Our expertise with sedation and analgesia management, patient and family communication, and interdisciplinary coordination can be readily extended beyond the ICU to dedicated in-patient hospice units, palliative care consult services, home hospice, and outpatient hospice facilities.

The utility of CCAs is not limited to improving clinical outcomes. Modern hospitals range from small community institutions to multi-billion-dollar enterprises employing tens of thousands. Their operations require leadership with expertise in emotional intelligence, team building, conflict resolution, and time-critical situational leadership; all key parts of the training and daily practice of the CCA. Hospitals at the top of US News and World Reports “Best Hospitals” list are more likely to be run by physicians.12 Those physicians require an understanding of how organizations operate from different perspectives. As intensivists from an anesthesia background, we understand the realities of shifting perspectives. Going from our “team of one” behind the curtain to rounding with a large group in the ICU. Single handedly managing mechanical ventilation, medications, and fluids for a single patient on a given day in the operating room, to delegating protocols to teams of respiratory therapists, pharmacists, and nurses for an entire service on another day.

The consequences of critical illness on long-term mortality risk are well documented, but information sharing between acute care and primary care settings is often incomplete and insufficient.13 Many primary care practitioners have limited direct access to medical records at larger hospital systems. For them, a patient’s ICU stay may become a black box filled with crucial but inaccessible information that will significantly impact the resumption of that patient’s care. As physicians whose practice ranges from the ambulatory to the ICU setting, we have a unique vantage point that can be used to institute programs connecting the entire spectrum of patient care. Information-sharing programs between intensivists and primary care providers have been shown to be a possible tool for improving numerous post-ICU outcomes.14 Such programs would allow easier transition back to the community and more targeted post-discharge care. These are likely to not only make life better for our patients but improve metrics tied to reimbursement, such as patient satisfaction, readmission rates, and referral numbers.

Academic production is another arena in which CCAs continue to make significant contributions. Those of us who enter critical care medicine tend to do so out of an innate curiosity for how the body is affected by the most severe physiologic insults. This is reflected in trends in publication patterns by CCAs. A recent review found that anesthesiology-trained authors outnumbered those from all other primary specialties in 3 of the 4 top critical care journals.15 Given the expanding need for ICU-level care, the need and opportunity for cutting-edge research led by ICU physicians will only grow.

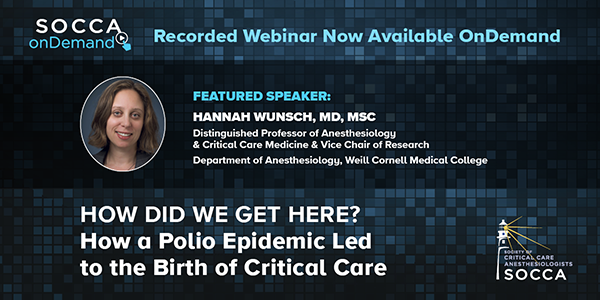

Critical care emerged as a concept from the 1952 Copenhagen polio epidemic.16 Since then, it has become a distinct, well-defined avenue of practice approachable from multiple specialties. The modern CCA is well poised to serve as a liaison between every part of the healthcare enterprise, including the operating room, wards, ICU, C-suite, and the community at large.

References:

- Gravenstein JS. Henry K. Beecher: The introduction of anesthesia into the University. Anesthesiology. Jan 1998;88(1):245-253. doi:Doi 10.1097/00000542-199801000-00033

- American Society of Anesthesiologists. The perioperative or surgical home. Washington, DC: American Society of Anesthesiologists; 2011.

- Harrison TG, Ronksley PE, James MT, et al. The Perioperative Surgical Home, Enhanced Recovery After Surgery and how integration of these models may improve care for medically complex patients. Can J Surg. Jul 23 2021;64(4):E381-E390. doi:10.1503/cjs.002020

- Andersen LW, Holmberg MJ, Berg KM, Donnino MW, Granfeldt A. In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Review. JAMA. Mar 26 2019;321(12):1200-1210. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.1696

- Lyons PG, Edelson DP, Churpek MM. Rapid response systems. Resuscitation. Jul 2018;128:191-197. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.05.013

- Szalados JE. Critical care teams managing floor patients: the continuing evolution of hospitals into intensive care units? Crit Care Med. Apr 2004;32(4):1071-2. doi:10.1097/01.ccm.0000119930.00644.41

- Combes A, Brodie D, Bartlett R, et al. Position paper for the organization of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation programs for acute respiratory failure in adult patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Sep 1 2014;190(5):488-96. doi:10.1164/rccm.201404-0630CP

- Gutsche JT, Vernick WJ. Cardiac and Critical Care Anesthesiologists May Be Ideal Members of the Mobile ECMO Team. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. Dec 2016;30(6):1439-1440. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2016.08.020

- Forum NQ. National voluntary consensus standards for quality of cancer care. 2009.

- Axelsson B. The Challenge: Equal Availability to Palliative Care According to Individual Need Regardless of Age, Diagnosis, Geographical Location, and Care Level. Int J Environ Res Public Health. Apr 1 2022;19(7)doi:10.3390/ijerph19074229

- White DB, Angus DC, Shields AM, et al. A Randomized Trial of a Family-Support Intervention in Intensive Care Units. N Engl J Med. Jun 21 2018;378(25):2365-2375. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1802637

- AK. G. Physician versus non-physician CEOs: the effect of a leader’s professional background on the quality of hospital management and health care. J Hosp Adm. 2019;8(5):47-51.

- Weissman GE, Harhay MO, Lugo RM, Fuchs BD, Halpern SD, Mikkelsen ME. Natural Language Processing to Assess Documentation of Features of Critical Illness in Discharge Documents of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Survivors. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. Sep 2016;13(9):1538-1545. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201602-131OC

- Zilahi G, O’Connor E. Information sharing between intensive care and primary care after an episode of critical illness; A mixed methods analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0212438. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0212438

- Karcioglu O, Karaaslan HN, Karcioglu AM. Who takes care of intensive care? Changes over the last two decades. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. Jun 2023;27(11):4842-4847. doi:10.26355/eurrev_202306_32600

- Lassen HC. A preliminary report on the 1952 epidemic of poliomyelitis in Copenhagen with special reference to the treatment of acute respiratory insufficiency. Lancet. Jan 3 1953;1(6749):37-41. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(53)92530-6