Emergent ECMO for a TE-Fistula: Fundamentals are Key

Introduction

This case report describes a young man who developed a tracheal-esophageal fistula (TEF) from endotracheal intubation with prolonged elevated cuff pressure after a traumatic fall. This case report describes the intra-operative management of profound hypoxia, shedding light on crucial pre-operative indicators that could serve as vital cues to prevent the occurrence of this potentially serious complication.

Case Summary

A 37-year-old man presented as a level 1 trauma after a fall from a second-story balcony. He had several injuries including subarachnoid hemorrhage, grade 1 blunt cerebrovascular injury, right temporal bone fracture, right iliac wing fracture, grade 3 liver injury, bilateral rib fractures, C7 transverse process fracture, right pulmonary contusion, and pneumothorax. He was brought to the hospital intubated for altered mental status and agitation. He was extubated on hospital day 4 only to be emergently re-intubated less than 24 hours later. He was unable to be weaned from the ventilator secondary to pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). After a discussion with the patient’s primary decision-maker, the team prepared him for tracheostomy and gastrostomy tube placement.

The percutaneous tracheostomy procedure was performed at the bedside after 8 days of mechanical ventilation. A bronchoscope via the endotracheal tube (ETT) was used during the procedure to visualize the needle, catheter, and dilators. When the tracheostomy tube (TT) itself was placed and the bronchoscope placed through the tracheostomy, the feeding tube was visualized which raised concern for esophageal placement of the TT. The ETT was advanced distal to the tracheostomy site. An additional attempt was made bedside to place the TT into the airway, however, despite good visualization of the guidewire with the bronchoscope, the TT continued to move into the esophagus. The patient was brought emergently to the operating room for neck exploration. The injury to the anterior esophagus was identified with an endoscope, through which the trachea and endotracheal balloon were seen. The Gastroenterology team was consulted and emergently deployed an esophageal stent.

Through the tracheoesophageal injury, the trachea appeared pale, ischemic, and ulcerated circumferentially. The patient remained hypoxic, and another attempt was made to place an open TT, but again, entry into the esophagus was made. The ETT was re-advanced past the injury. Post-advancement, the patient became profoundly hypoxic. The ECMO team was consulted intra-operatively, and the patient was deemed a candidate. Inhaled nitric oxide therapy was initiated while awaiting cannulation to Veno-Venous (V-V) ECMO. The neck was closed, and the patient was prepared for cannulation.

Following 23 days on V-V ECMO, the patient underwent decannulation. Ten days later, he underwent definitive repair of his TE Fistula with tracheal resection. After a culminative 70 days in the hospital, he was discharged to a long-term acute care facility.

Case Discussion

Tracheo-esophageal fistula (TEF) formation is a rare complication of endotracheal intubation, thought to occur in less than 1% of patients1. In this patient population, it is reported that up to 65% could receive a secondary TEF due to overinflation of the cuffs2. Further risk factors for TEF formation include trauma and cancer. Risk factors for development include rigid nasogastric tube, poor nutritional status, respiratory infections, and agitation/TBI leading to excessive head movements3,4—all of which were present in this patient. The culmination of these risk factors led to increased difficulties with his management.

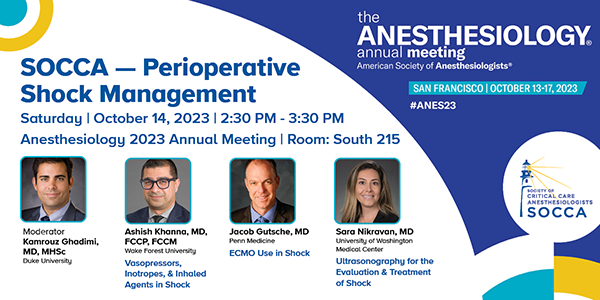

High-volume, low-pressure endotracheal tube cuffs adoption has decreased the incidence of TEF formation. However, measuring and reporting cuff pressures is still necessary. It is thought that cuff pressures greater than 30 cm H2O contribute significantly to mucosal ischemia1. In our institution, the respiratory therapist measures and reports at least twice a shift; the lead respiratory therapist reports this during rounds with the team.

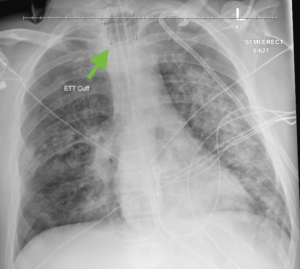

Factors such as a cuff leak or severe agitation leading to excessive head movements can also contribute to TEF formation. In this case, excessive cuff pressures were not reported to the team, although a cuff leak was noted intermittently. The patient was initially very agitated; we were unable to assess from the notes the extent of this. This patient had daily x-rays, sometimes several times a day, and there were several in the days leading up to the bedside tracheostomy where the endotracheal cuff was visibly enlarged.

Importantly, this case highlights the importance of critical care fundamentals. Paying careful attention to each detail in the patient chart, as well as a multidisciplinary approach during rounds can ensure the full complexity of each patient’s care is thoroughly managed. A systematic approach to the evaluation of the intubated patient is important. Beginning with a physical assessment, an assessment of the ventilator, followed by a review of imaging is a reasonable approach to use when in the ICU.

References

- Mooty RC, Rath P, Self M, Dunn E, Mangram A. Review of tracheo-esophageal fistula associated with endotracheal intubation. J Surg Educ. 2007 Jul-Aug;64(4):237-40. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2007.05.004. PMID: 17706579.

- Muniappan A, Wain JC, Wright CD, et al. Surgical treatment of nonmalignant tracheoesophageal fistula: a thirty-five-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95(4):1141-1146. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.07.041

- Green MS, J Mathew J, J Michos L, Green P, M Aman M. Using Bronchoscopy to Detect Acquired Tracheoesophageal Fistula in Mechanically Ventilated Patients. Anesth Pain Med. 2017 Jul 22;7(4): e57801. doi: 10.5812/aapm.57801. PMID: 29430408; PMCID: PMC5797673.

- Kaur D, Anand S, Sharma P, Kumar A. Early presentation of postintubation tracheoesophageal fistula: Perioperative anesthetic management. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2012 Jan;28(1):114-6. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.92460. PMID: 22345958; PMCID: PMC3275943.

Image 1. Chest X-ray from the morning of bedside tracheostomy. Note the enlarged endotracheal tube cuff, likely due to overinflation.