Introducing the SOCCA Service Chiefs’ Advisory Council

As a professional organization dedicated to the support and development of anesthesiologists who care for critically ill patients, SOCCA’s aims include fostering community and advocacy. SOCCA has therefore organized and promoted efforts to better understand the national anesthesiology critical care practice landscape. Two such efforts—respective surveys of the SOCCA and American Society of Anesthesiologists membership—have yielded valuable insights [1, 2]. However, our conceptualization of the national landscape remains incomplete. Organizational membership surveys, by definition, reach only members of those organizations and reflect only the responses of those who choose to participate, which serves to introduce bias. For example, compensation as self-reported in such surveys will be naturally weighted to reflect the prevailing standards at the institutions with the most respondents, and those standards themselves will be highly influenced by local or regional market forces and institutional culture.

Additionally, as an organization, SOCCA has a vested interest in understanding national clinical, operational, and administrative challenges informed by those who are tackling such problems. For SOCCA and other national professional organizations, committees composed of member volunteers form the backbone of such efforts but risk losing valuable perspectives from those without an organizational affiliation or those otherwise without a seat at the table owing to myriad factors. Committees may therefore not offer truly representative viewpoints.

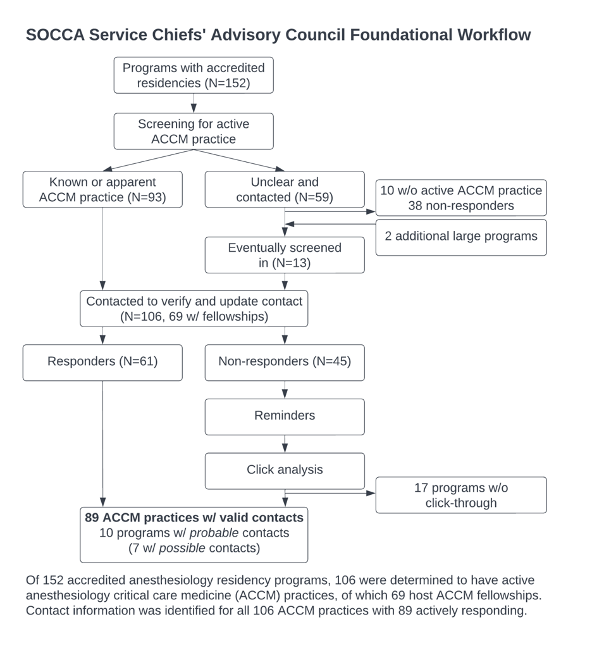

In response to these challenges, SOCCA has aimed to create a nationally inclusive, organizationally representative body that we have termed the Service Chiefs’ Advisory Council. Patterned off the anesthesiology critical care medicine fellowship Program Directors Advisory Council (PDAC), the approach was to identify the one or two individuals at each institution with the broadest operational or administrative purview over their institutional anesthesiology critical care practice. Depending on the size and scope of the local practice, this might be a critical care organization (e.g., center or department) leader, a departmental vice chair for critical care, a division head, a unit medical director, or a senior physician in smaller practices. In contrast to the PDAC, there is no centralized repository of individuals in these roles (e.g., akin to a program director listing maintained by the ACGME), so one had to be created.

The aforementioned survey data suggests that the majority of anesthesiologists practicing critical care are in academic settings. Additionally, the ACGME mandates that anesthesiology trainees complete four months of critical care training with at least two of those including exposure to faculty anesthesiologists experienced in critical care. As such, we began by assuming that each ACGME-accredited anesthesiology training program would have a non-zero critical care practice. Identifying community anesthesiology critical care practices and ensuring their representation on the Council remains an important but incomplete next step.

This effort ultimately yielded contact information for 106 active anesthesiology critical care practices. Each institution was asked to identify a primary contact, a secondary contact, and (where applicable) an administrative contact to aid with maintenance of the directory over time. In an order to promote maximal representation, the Council’s constituents need not be active SOCCA members. SOCCA will continue to provide logistical support, and Council members interested in leadership positions will need to be active members per SOCCA’s bylaws.

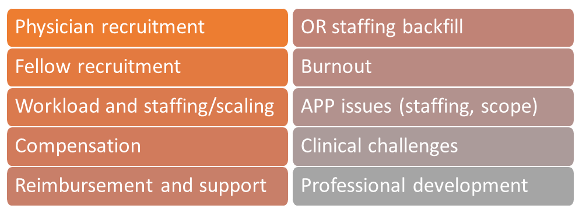

The broad aims of the Council are to improve SOCCA’s line of sight into operational challenges, clinical challenges, organizational structures, and physician recruitment at the institutional level. More broadly, we aim to foster awareness about impacts of the national practice landscape, regulatory changes, reimbursement, and competition on anesthesiology critical care medicine. For the Council’s constituency, aims include facilitating collaboration, networking, and mutual assistance while also identifying collective priorities and a leadership structure. To that end, Dr. Anne Drewry was recently named as the Council’s Vice Chair, and Dr. Sheida Tabaie will serve as Secretary. Thematic analysis of a start-up survey yielded multiple shared interests and priorities, which will help to inform the Council’s first collective work product.

Looking ahead, the Council also needs ongoing structural development. While representation from 106 active programs is an inspiring start, there are likely more nationally that are not yet represented, particularly in the community. If you are in such a practice or know of a sizable community practice locally with anesthesiology critical care leadership, please do reach out with contact information to help us ensure that the Council develops into a truly inclusive body.

References

- Shaefi S, Pannu A, Mueller AL, Flynn B, Evans A, Jabaley CS, et al. Nationwide clinical practice patterns of anesthesiology critical care physicians-a survey to members of the Society Of Critical Care Anesthesiologists. Anesth Analg. 2022:Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35950751.

- Siddiqui S, Bartels K, Schaefer MS, Novack L, Sreedharan R, Ben-Jacob TK, et al Critical care medicine practice: a pilot survey of us anesthesia critical care medicine-trained physicians. Anesth Analg. 2021;132(3):761-769. PMID: 32665465.