Now is Our Moment: A Call for Mentorship

Interview Subjects:

Rebecca Aslakson, MSci, PhD, MD, is a triple-boarded physician in Anesthesiology, Palliative Care Medicine, and Surgical Critical Care, and is the Chair of the Department of Anesthesiology at the Larner College of Medicine at the University of Vermont.

Rebecca Aslakson, MSci, PhD, MD, is a triple-boarded physician in Anesthesiology, Palliative Care Medicine, and Surgical Critical Care, and is the Chair of the Department of Anesthesiology at the Larner College of Medicine at the University of Vermont.

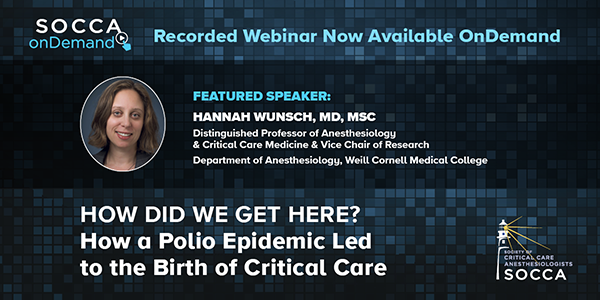

Hannah Wunsch, MD, MsC is an author, anesthesiologist, and intensivist in the Department of Anesthesiology, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York.

Hannah Wunsch, MD, MsC is an author, anesthesiologist, and intensivist in the Department of Anesthesiology, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York.

I recently had several conversations with rising women medical students and residents wanting to know more about anesthesiology and critical care medicine as a career. Typically, in these situations, I think many of us feel compelled to give “the pitch” for why our lives are so great. And yes, recruitment into our subspecialty, particularly for women, is severely needed.

But we know that our specialty, compounded between anesthesiology and intensive care, is a profession at high risk for burnout and exhaustion. Aside from clinical responsibilities, women also contribute a significant time to “invisible work” – that is, work that requires time and effort but is not recognized by common metrics both professionally and in our personal lives. When these aspiring intensivists reach out to explore our career path, I sometimes walk away from these conversations unsatisfied. What is, or should be, our goal?

When reflecting on the questions these women ask, most of them aren’t asking for the generic answers of perioperative management of patient care in the operating room and intensive care unit, the fulfillment of treating complex physiology, etc. Those are easily demonstrated in the literature and with online searches. What these women want to know is not why we do it, but how we do it. It is incumbent upon us for the successful careers of future generations of women intensivists that we do not play Oz in the back room and simply put on a good show. We owe it to the next generation to pull the drapes back and reveal the inner workings of our lives.

Mentorship is essential for this mission; however, we are all susceptible to the lack of protected time and the limited number of experienced mentors. In fact, some studies suggest women carry a higher responsibility for mentorship, but without recognition in academic promotion or metrics for advancement (note again the invisible work), and without having mentors ourselves (2Shen MR, et al.). The Push-Pull Mentoring Model ([1]Silver, et al.) provides a bidirectional approach to mentorship, suggesting active participation by both the mentor and mentee contributing to a symbiotic relationship with academic and career productivity for both.

As this September recognizes Women in Medicine, let us alter our framework to become the Lion, the Scarecrow, and the Tin Man for our mentees, to help them navigate this career path and ultimately mentor them to become successful guides themselves. Below we asked expert women mentors in anesthesiology critical care medicine for suggestions on how we accomplish this mission:

Dr. Rebecca Aslakson, MSci, PhD, MD, is a triple-boarded physician in Anesthesiology, Palliative Care Medicine, and Surgical Critical Care, and is the Chair of the Department of Anesthesiology at the Larner College of Medicine at the University of Vermont.

In your opinion what are the qualities that enhance a good mentor-mentee relationship?

Dr. Aslakson:

I think the most important quality in a good mentor-mentee relationship is earnest mutual respect and appreciation for each other. Along with that, good listening on both parts is key; with good listening to each other, the mentor can best understand the needs and goals of the mentee and the mentee can better process and utilize what advice the mentor has to give. As both mentor and mentee, my most rewarding relationships have been the ones where we honestly appreciate, respect, listen to, and enjoy each other as people and colleagues.

It is not easy to find time and passion for mentorship, how do you stretch yourself?

Dr. Aslakson:

Mentorship is not one-size-fits-all for every relationship, and that is a good thing. Sometimes you have more to give and other times you have less. It is important to just be honest and, if needed, to set limits with mentees. There are some mentees where we have a longitudinal, deep relationship that clearly has significant time invested on both sides. Then there are others where I might meet with them once or twice a year, and that is sufficient for both of us. Sometimes being able to offer only a little interaction, such as a single call or meeting, is still better than nothing and can start the person on the path to find a mentor who can make a more significant time investment. Also, clarity is a gift; if I recognize that I cannot be the mentor that a mentee would want, it is a gift to them to honestly say “no” and to help them find someone else. Knowing and respecting your own limits is important for self-care and it also is important for your mentees to see (and model).

What would you tell new mentors that you wish you had known before you embarked on these relationships?

Dr. Aslakson:

No one knows everything. Keep humble but also recognize that you have worked multiple years in the field, you have good experience, and you have good things that can help others. Also, a big part of being a good mentor is taking the time to listen; I feel like I have helped some of my mentees the most not through what I said but by giving them the space to talk through their thoughts and experiences. I have helped them the most by being someone with whom they can plan next steps forward. So never underestimate the incredible importance and value of being a sage, thoughtful, and wise listener for your mentees.

What advice would you give to mentees to contribute to the mentor-mentee relationship, and how can this promote advantages for both mentee and mentor?

Dr. Aslakson:

I really like when my mentees approach our meetings with agendas; the day before we are meeting, they email me a tentative agenda for what they would like to discuss. It helps me to prepare so I am ready for the meeting. The agenda also enables the mentee to prioritize their goals and what they want out of our meeting. I find that having an agenda (it can be tight or loose) helps my mentee and I to be markedly more productive in our meetings.

How does mentorship intersect with increasing diversity and inclusion?

Dr. Aslakson:

Mentorship is a major tool by which one can improve diversity and inclusion within a group. It is very hard to be what you do not see and thus, as individuals who are underrepresented in leadership rarely see people like them in leadership, they are consciously and unconsciously less likely to promote themselves as potential future leaders. Yet, with mentorship, you can actively short-circuit that negative pathway. By actively mentoring, sponsoring, and coaching individuals from underrepresented communities, you can help them to recognize their own potential, to more smartly leverage and work their way through the system, and to set themselves goals that they would not otherwise have thought possible.

How can mentors bridge social capital among similar groups? Bridging social capital describes the process of uniting individuals of diverse backgrounds to encourage collaboration, understanding, and the exchange of resources.

Dr. Aslakson:

The biggest thing is to connect your mentees across different domains. You likely exist in multiple domains in your career; for example, I am a critical care anesthesiologist and palliative care physician and researcher as well as the Chair of a Department of Anesthesiology. Thus, I have different “circles” of colleagues from critical care practice, critical care research, palliative care practice, palliative care research, administrative leadership, etc. I also have mentees in each of those different domains. One of the most helpful things that I can do is to bring together people across domains who might not have otherwise met but who could likely potentiate each other. Thus, I would encourage mentors to think about all of the different domains in their own career and to be open to thinking about how to connect people across them.

Dr. Hannah Wunsch is an author, anesthesiologist and intensivist in both the Department of Critical Care Medicine at Sunnybrook Hospital and Professor in the Division of Critical Care Medicine at the University of Toronto.

How does mentorship intersect with increasing diversity and inclusion?

Dr. Wunsch:

Only through good mentorship can we increase diversity and foster inclusion. Mentorship is a way to show the next generation what successful, but also inclusive, working environments look like. While it may help to have mentors who themselves are diverse, I think mentors who may come from more traditional backgrounds can still help enormously to increase diversity and a sense of inclusion by the way they interact with others, and whether the environment in their lab, or research group, or more generally, feels welcoming, non-judgmental and supportive. It is also important to educate oneself about what the specific challenges are for different people. The topics addressed in discussions and the focus of the mentorship needs to be tailored to focus on whatever the specific challenges are for an individual, whether due to culture, or family background, or personality.

In your opinion what are the qualities that enhance a good mentor mentee relationship?

Dr. Wunsch:

Trust is a big one. Both mentor and mentee have to trust each other. The mentor needs to know that the time and energy invested in a mentee are valued (and also respected) and that the mentee will make good use of the advice and support. The mentee needs to feel confident that the motivation of the mentor is one that is focused on excitement about seeing the mentee succeed, rather than about their own success or promotion. Both need to be committed to the relationship.

For a mentor, it’s important to let go and allow a mentee to make some mistakes along the way and then also help them build confidence in their own judgement. Otherwise, there can be too much reliance on the mentor for advice at every single step. However, I think it’s also important for a mentor to know when to step in and help a mentee avoid wasting time. Finally, I think a real key to the relationship is to recognize that ultimately each individual’s journey is about whatever makes them happy; this may not be the path the mentor is on, and it also may not be the path a mentor recommends.

It is not easy to find time and passion for mentorship, how do you stretch yourself?

Dr. Wunsch:

Mentorship is so important that it’s essential to find time for it. However, mentorship can take many forms, and sometimes it’s just a sporadic chat with someone at a conference, or a quick call a few times a year – these can be very rewarding relationships on both sides.

That said, for more traditional mentoring, which is a big-time commitment, I do think it’s important not to take on mentorship of too many people at once. While sporadic mentorship may be appropriate in some situations, in general, the mentor/mentee relationship requires a real commitment and availability. I also think it’s a mistake to take on too much mentorship early in one’s career. There are different phases in a career, and while peer mentorship can be great, it’s hard to carve out time when you are yourself career-building.

What would you tell new mentors you wish you had known before embarking on these relationships?

Dr. Wunsch:

Not every person looking for a mentor is someone you can mentor yourself. This may be because you are over-committed, their research interests or career focus don’t align with yours, or because their personality is just not a good fit. I think it’s much better to help guide such individuals to others and to recognize that you can’t be a great mentor to all who need mentorship. That said, I’ve also been surprised as a mentee myself as to how meaningful and helpful even a single conversation with someone can be, often with people who are at different institutions or from different backgrounds. So, I also encourage people to be willing to meet, even if it’s just for a chat. Those can sometimes be life-altering conversations.

How can mentors bridge social capital among similar groups? Bridging social capital describes the process of uniting individuals from diverse backgrounds to encourage collaboration, understanding, and the exchange of resources.

Dr. Wunsch:

One way I try to facilitate this is by having a weekly “lab meeting.” I don’t run a lab, but the idea is modeled on such meetings (I worked in a basic science lab as an undergraduate). To me, this is an opportunity for coming together as a group – ideally in person, although virtual can work as well. And it’s an opportunity to hear what others are working on, to exchange ideas, and to just force everyone to interact and share ideas. A lot of research (or clinical work) is spent off on one’s own and so I think circumscribed discussion time is essential to help connect people. This is also true of more purely social events. I think it really helps people to come together socially as an opportunity to get to know each other, when there is a shared interest, such as a research area or clinical focus.

Something I noticed after COVID-19 was that more junior mentees didn’t appreciate the value of attending conferences in person because they’d never had the opportunity! I encourage people to go to conferences as I think it is such a key way to forge relationships with like-minded individuals at other institutions and in other areas. So many of my main friendships and collaborations in my own work were formed standing in front of posters and at coffee breaks, and so I feel we need to really reinforce the importance of such interactions.

What advice would you give to mentees to contribute to the mentor-mentee relationship, and how can this promote advantages for both mentee and mentor?

Dr. Wunsch:

Honesty is key. A mentor can only provide useful support and advice if a mentee is honest about what they want to be doing and what they care about. It’s a danger that the mentee wants to say the right things to “please” the mentor. But this doesn’t benefit anyone.

Related to that is the importance of the underlying tenet that people need to make choices and spend their time in ways that will make them happy. Both mentor and mentee must remember this. I think it’s very important always to have frank conversations about individual goals and aspirations, mental health, and the importance of prioritizing family (and friends) in one’s life.

1-Silver JK, Gavini N. “The Push-Pull Mentoring Model: Ensuring the Success of Mentors and Mentees.” J Med Internet Res. 2023; 25: e48037. Published online 2023 May 25. Doi: 10.2196/48037

2-Shen MR, Tzioumis E, Andersen E, Wouk K, McDall R, Li W, Girdler S, Malloy E. “Impact of mentoring on academic career success for women in medicine: A systematic review.” Acad Med. 2022 Mar 01;97(3):444-458.