Program Director Q&A

Dr Matt Wiepking is the Program Director for the Anesthesia Critical Care Medicine Fellowship at the Los Angeles General Medical Center and the University of South California, he has served in this role for the past 2 years.

Dr. Pannu: What are some of your favorite parts of being a critical care medicine fellowship program director?

Dr. Wiepking: The program design and improvement aspect is hugely satisfying, and you get to see the ripples of your efforts across the institution’s larger educational and clinical environment. Mostly, though, I enjoy being a resource and a sounding board as our fellows navigate the highs and lows of fellowship—as we all know, ACCM fellowship is a challenge on many levels! There is something very unique and powerful about seeing our fellows go from figuring it all out in July, to leaders in the ICU by the end of their training. Recruitment time- when we meet all the residents interested in critical care- is also always a blast!

Dr. Pannu: What are some challenges program directors are facing today?

Dr. Wiepking: Fellowship recruitment remains challenging- which is not a surprise to most readers of the Interchange. The pandemic brought CCM to the front and energized many people but also highlighted the rigor and demands of this job and highlighted how we must continue to make this sustainable. More recently, the job market for anesthesiologists has been very favorable, often cited as a factor for decreased interest in subspecialty training overall. However, there are many reasons to be optimistic about this year’s Match as well (see Dr Fiza’s piece for more info!)

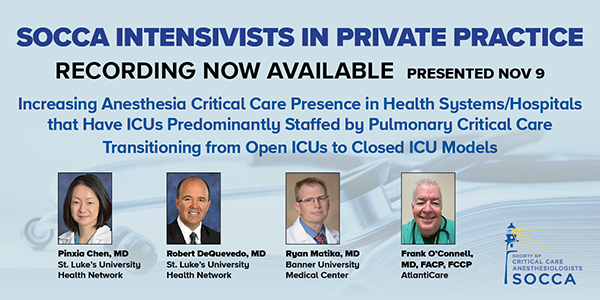

As a program director, I would also love to see some ongoing focus on highlighting and exploring careers outside academics for Anesthesia Critical Care. Intensivists are needed everywhere, and our training prepares us to succeed across the critical care landscape. The Intensivists in Private Practice and similar groups are key to highlighting intensivists’ role in non-academic practice models.

Dr. Pannu: What advice would you give to medical students and residents considering a career in critical care medicine? What is something you wish you had known?

Dr. Wiepking: The most significant thing is that critical care contributes significantly to my personal and professional satisfaction. While undoubtedly a challenging field because of the complexity and degree of illness and the emotional toll on patients, family, and staff, you also have some incredible highs of seeing your patients get better, get stronger, and get home. Working in the ICU allows us to engage in the full spectrum of care and connect on a deeper level with the journey our patients and their loved ones go through as we face critical illness together.

My advice to our medical students and residents thinking about a career in critical care would be to reach out and ask questions. Talking with fellows and faculty who embarked on this amazing path helped me visualize what my life and career can look like, so I recommend getting informed and embracing the differences in practice that critical care can offer you. Yeah, you’ll round—so what? You’ll also come out highly knowledgeable and capable in an actual crisis and be given plenty of opportunity to push your EQ higher. Clinical skills, life skills, balloon pumps, bowel regimens—we have it all. Apply today.

Dr. Pannu: What are some advances you foresee in the practice of critical care medicine? What role do you foresee critical care anesthesiologists and SOCCA playing?

Dr. Wiepking: Anesthesia-trained intensivists bring immense value to any ICU thanks to their deep understanding of hemodynamics, procedural skill, and often the uniqueness of their perioperative experience. They have led the field in training physicians from multiple disciplines and I hope that this continues.

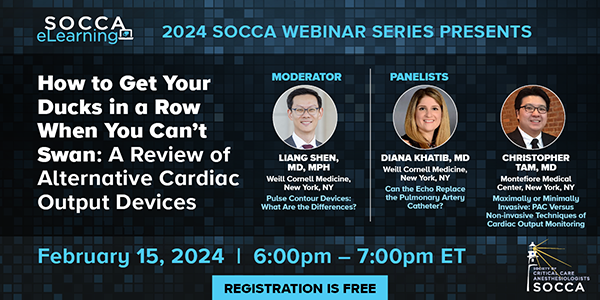

Secondly—and I’ll show my bias here as someone who got hooked into this world from fellowship on—I think there’s a lot of energy going into temporary circulatory support. I am interested in seeing how those technologies may become more durable and portable. There are some really challenging, emotionally charged, and ethically complex realities that arise as these technologies become more effective at generating and maintaining perfusion. Given that anesthesia-trained intensivists often work in units that use these technologies, we have a significant role to play in advocating how to address this frontier in medicine and bring our referring physicians, consultants, patients, and families together to develop a shared mental model of how and when to use these powerful tools.